The COVID-19 crisis has affected us all, but its impact on working women has been devastating. Within just a few months, female participation in Canada’s labour force plunged to its lowest level in 30 years, driven by layoffs and shifts in how we live and work.

The fallout now threatens to ravage the pipeline of next-generation female leaders, potentially reversing much of the progress corporate Canada has made towards diversity and inclusion and creating an economic performance gap that will impact us all.

Unlike the Great Recession of 2008, during which eight-in-10 job losses affected men, female workers have borne the brunt of layoffs this time around and are returning to work at a slower pace. What’s more, the pressures of juggling jobs, family and household responsibilities have fallen disproportionately to women, significantly affecting their productivity and mental well-being, and leading an alarming number to consider leaving the workforce entirely.

To understand the impact of the pandemic on corporate equity, we talked to a range of diversity and governance experts about the steps companies and policy makers can take to protect the gains to date and assure future progress. What we learned suggests that Canada is at a crossroads. If we continue on our current path, we risk losing vast resources of critical talent, the impact of which could last for decades. Alternately, by seizing the moment to build on the heightened attention to equity and the urgent need to set the global economy on the path to recovery, Canadian businesses can join their counterparts around the world in accelerating the participation of women at all corporate levels.

Gender equity propels corporate performance

As a long-term investor, we consider it our responsibility to ensure the boards and management teams of our investee companies see diversity not just as a number on a page, but as a genuine lever to effect better investment outcomes. Our mandate to help protect the retirement security of 20 million Canadians gives us a role to play in promoting practices that enhance investment returns and benefit the economy.

Hundreds of studies have established that companies with diverse boards and leadership, where a range of experiences, backgrounds and perspectives feed better decision-making, are more likely to achieve superior performance. To cite just one recent study, companies in the top quartile for management gender diversity were 25% more likely to deliver above-average profitability than those in the bottom quartile; ethnic and cultural diversity produced even higher gains.

Additionally, research suggests that diversity makes companies more resilient during crises. A study that analyzed the Great Recession found companies that maintained an inclusive environment flourished while those that didn’t floundered, and that banks run by women and with a higher share of women on their boards were more stable than their peers. The current crisis is already displaying similar patterns, from corporate performance to investment returns.

But today we face a unique danger. Over the course of the pandemic, 30% of women in the workforce have considered leaving their jobs, compared to fewer than 20% of men, according to Catalyst. Recent data from Lean In shows that one-in-four women are considering downshifting their careers or leaving the workforce. Many women, especially those in mid-career, face a difficult dilemma: to lean in to work as offices start to re-open, or to cut down on their hours or quit altogether in order to look after children who remain at home.

“My biggest fear is that a lot of women end up taking a slight step back by taking leaves of absence, saying no to work opportunities or reducing their hours, and that ends up impacting their entire career trajectory,” says Camilla Sutton, president and CEO of Women in Capital Markets (WCM).

Time for genuine change

Even before the pandemic, Canada’s pace of progress toward gender parity in corporate leadership and governance was disappointing, to say the least. Some opt for stronger language: “appalling,” “abysmal” and “embarrassing” are just three adjectives we heard from the men and women we interviewed. There are 179 companies listed on the TSX with no women on their board. A mere 19% of board seats at publicly listed companies on the TSX are filled by women. Given the amount of attention and money devoted to addressing equity, these results are unacceptable.

So, what do we do? Our research, stakeholder discussions and consultations with experts have led us to seven recommendations for businesses, investors and policy leaders to preserve the pipeline of women business leaders.

Read our paper, Voices of Inclusion, for more insights from the leaders cited throughout.

1. Set measurable diversity targets for board seats and executive positions

To date, Canada has relied largely on stakeholder pressure, public scrutiny and moral suasion to encourage progress on leadership diversity. Given the paltry gains, voluntary measures such as “comply and explain” have produced, that approach clearly hasn’t worked. Even though many boards still lack female directors, 67% of board vacancies last year were filled by men.

The time for wishful thinking is over. The support for adopting targets around female representation at board and executive levels of publicly listed companies is high, with 92% of capital markets respondents backing such measures in a recent poll.

At the very least, we need to do away with that insulting excuse “we couldn’t find any qualified women.” FCLTGlobal CEO Sarah Williamson, whose organization promotes a long-term focus in investing, compares the excuse to a salesperson telling the boss: “We couldn’t find any customers.” Where did you look? Whom did you ask? What share of candidates were women or racialized individuals?

Beth Stewart, CEO of Trewstar, a board recruitment firm that focuses on diverse directors, says her company offers to present its clients with all-female slates and asks them to interview those women first. The firm expands the candidate pool to men if the client finds no suitable candidate and requests the addition of men. In more than 130 searches that started with an all-female slate, Trewstar has yet to receive such a request.

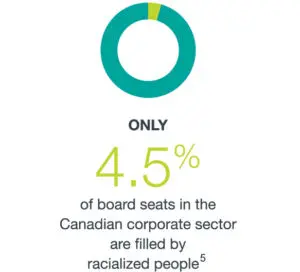

The Black Lives Matter movement has rightly increased stakeholder attention on equity beyond gender. A recent study found that representation by racialized people on Canada’s corporate boards stood at a mere 4.5%. Some directors serve on the same boards for decades, preventing renewal. Yet the senior members of these boards often refuse to engage in the unpleasant conversation of telling a fellow director, “Thank you for your service, we don’t need you to stand for re-election this year,” says Stewart. To free up seats for diverse candidates, it’s time to look more closely at how board renewal takes place.

Boards should implement an annual process for evaluating the effectiveness of the board as a whole, its committees and each director individually. The process should focus on evaluating the need for any board membership change to ensure that the board as a whole has the necessary experience, qualifications and diversity to serve the interests of the company. In evaluating its own effectiveness, the board should also consider whether it is sufficiently focused on the long-term best interests of the company. Directors who underperform should be asked to resign.

2. Build the talent pipeline

Ultimately, fulfilling any diversity targets for leadership and governance requires boosting the talent pipeline, and that means tracking diversity at all organizational levels. “Everybody says, ‘We’ve got to close the gap,’ but how can you close a gap you haven’t measured and don’t know where the gap is?” asks Caroline Codsi, founder of Women in Governance.

“Everybody says, ‘We’ve got to close the gap,’ but how can you close a gap you haven’t measured and don’t know where the gap is?” asks Caroline Codsi, founder of Women in Governance.

Start with recruitment: organizations should set goals for attracting under-represented groups and track progress as closely as they do for any other business objective. Consider where you are recruiting from—is it always the same business schools? Is your recruiting team itself diverse? Then apply a similar approach to promotions by requiring business units to put forward multiple candidates from under-represented groups for each leadership opening, and then to report on these employees’ advancement. Such data can show companies if there are “cliffs” along the organizational path that we have a collective responsibility to address, notes Norie Campbell, who leads the Inclusion & Diversity Leadership Council at TD Bank. “Are women charging along as mid-level managers and suddenly going off the representation cliff at the next level? Are there reasons embedded in the job expectations that give us insights we need to act on to eliminate the cliff?”

Making the progress visible to all can build engagement throughout the organization. One major Canadian energy company, for example, has a diversity dashboard open to all employees that is continually updated. At KPMG in Canada, where women form the majority of the leadership team, every hire and promotion is reviewed for potential diversity bias, and maintaining a pipeline of female and visible-minority talent is one of the criteria in executive performance reviews. “We need to create opportunity in the middle as well as the top of the organization,” says CEO Elio Luongo. “It takes time to build that pipeline, but that shouldn’t be an excuse.”

The role of institutional investors

Investors, especially large institutions such as pension funds, need to exercise their ownership influence to encourage practices that lead to sustainable value creation, including governance and leadership diversity.

CPP Investments holds more than 200 board seats in both public and private companies around the world, and we have been using our Global Gender Diversity Voting Practice to increase gender diversity within our investee companies—first in Canada and now globally.

We have been steadily ramping up the pressure. In 2017, we cast votes at shareholder meetings and tried to engage with 45 Canadian companies that had no female board members; a year later, nearly half of those companies had appointed a female director. In 2018, we escalated this practice by voting against all nominating committee members at companies where we had voted against the committee chair in 2017 if the company had made no progress at improving board gender diversity.

Last year, we went further still, voting against nominating committee chairs of S&P/TSX Composite Index boards with fewer than two female directors. We also extended our voting practices to non-Canadian boards, voting against the election of 626 directors globally during the 2019 proxy season due to diversity concerns.

There are signs of progress. In 2019, Canada’s TSX 60 Index-listed companies achieved 30% female representation on boards. According to a new report by Catalyst and the 30% Club Canada (of which CPP Investments is a member), the percentage of women on the boards of S&P/TSX Composite Index companies rose from 18% to 28% in the past five years, and they now constitute 18% of the executive teams, up from 15%.

Investing institutions should also serve as role models for corporate diversity, a challenge we take to heart.

We committed to, and in 2019 reached, 50/50 gender-balanced hiring. Today, 43% of our investment professionals, and 22% of senior investment managers, are women— and we are on track to reach 30% representation company-wide by 2025. We have received Women in Governance Gender Parity certification, which acknowledges a measurable commitment to advancing women. We have also introduced firm-wide initiatives to foster inclusive behaviours of empathy, humility and authentic curiosity, such as our mandatory firm-wide training on managing inclusively and mitigating biases. Additionally, we have committed to hiring at least 5% of our student workforce from the Black community and 3% from Indigenous communities. Finally, our Head of Diversity and Inclusion reports jointly to the President & CEO and the Chief Talent Officer—a signal that equity is a central concern at the highest executive level.

3. Support childcare for working parents

The additional burdens placed upon unpaid caregivers—many of them women—by schools going virtual, and the shuttering of daycares and recreational services, have not abated. While more men did pitch in with domestic duties during the pandemic, a third of female respondents in a recent poll reported they still shoulder the majority of household chores and caregiving responsibilities. Working men are also almost twice as likely as working women to have partners without full-time jobs who can shield them from domestic responsibilities. It’s not surprising, then, that employment rates for mothers of toddlers or school-aged children fell by 7% between February and May, significantly more than it did for men. Furloughs and reduced hours may turn into permanent departures if parents who lack childcare are forced to put their professional ambitions on hold. “I think we’re going to see a second wave as schools and companies go back, with a mass exodus of women from the workforce,” says Sarah Kaplan, professor and director of the Institute for Gender and the Economy at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management.

In response, calls have been growing for increased childcare support to enable more women to return to work. Canada has underinvested in childcare, says Kaplan, pointing out that we are far from achieving the benchmark of 1% of GDP set by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) for childcare investment. As the federal government noted in the recent Speech from the Throne, governments need to make childcare more affordable and accessible across the country. Business should play its part by establishing more on-site daycares, helping employees source childcare, and accommodating workers who cannot return to the office because their children remain at home.

Putting greater focus on parental leave is another important tool. Canada’s rate of female workforce participation rose significantly compared to that of the U.S. in 2000, when our country extended maternity leaves. However, a lengthy absence during prime working years can exact a penalty on a woman’s career advancement. Women already face a “broken rung” on the corporate ladder in their first step up to the manager level—typically in their 30s or 40s, when home life tends to be most intense—where only 72 women are hired or promoted for every 100 men. Encouraging fathers to take more leave will help even the playing field, says Tanya van Biesen, Senior Vice President, Global Corporate Engagement at Catalyst, but that requires combatting the still-lingering stigma put on men who take time off to care for children.

4. Combat bias in the corporate culture

Gender-blind is not the same as gender-neutral. We see what we want to see and have been accustomed to seeing: when financial sector employees were asked to agree or disagree with the statement “In my experience, my workplace is free from gender bias,” for example, almost twice as many men agreed as women.

When it comes to board appointments, bias can show up in the qualifications demanded of female candidates. “You need to be a lawyer and in finance and have an MBA and a CFA,” says Codsi. Very few women or men could muster such CVs, but boards feel they need to overcompensate “because they are convinced that, if they choose a woman, it’s risky,” she says.

The reality is that decision makers may not consciously exclude people, but neither do they consciously include the broadest pool of candidates. One way to combat personal and organizational biases is to re-examine each part of the system, each policy, each process: by creating formal criteria for leadership positions (including skills that are traditionally less valued, such as relationship building), for example, and using them to guide interviews, offer feedback and conduct performance reviews. If you have standardized questions around hiring and promotion, and you put a diverse candidate pool in front a diverse hiring panel, the risk of some candidates leaning on informal relationships, such as those built on the golf course or on sports teams in which women aren’t invited to participate, drops. To avoid that risk, some companies run job descriptions through software programs that remove terms that may appeal more to men than women.

5. Go beyond diversity to inclusion

Diversity is just a first step in achieving equity. Women and minorities regularly report a higher incidence than men of so-called micro-aggressions, such as being excluded from social events or hearing derogatory comments. Such experiences go to the heart of inclusion, which is different from diversity. “When you look at diversity, you’re focused on the individual,” says Campbell. “When you focus on inclusion, you’re focused on how your organization works.”

Inclusion-related behaviours are subtle, but they make a big difference in how employees perceive their work experience and leadership potential. In a McKinsey survey, 39% of respondents said they have turned down or decided not to pursue a position because of a perceived lack of inclusion at the organization. The corporate culture, and how it’s expressed, can send strong signals. Does the manager’s office look like a man cave, covered in sports memorabilia, for example?

Some signs of an inclusive culture are counterintuitive, such as giving constructive coaching, including criticism, to all employees. “If you look at people who’ve been successful, almost by definition somebody has taken a risk on them and given them negative feedback,” which is essential for improvement and growth, says Williamson. But managers may hesitate to criticize employees who are different from them for fear of repercussions. “We see in the data time and again that women are promoted for performance and men are promoted for potential,” she says. “And if you are only promoted for performance, you don’t get the opportunity.”

“If you look at people who’ve been successful, almost by definition somebody has taken a risk on them and given them negative feedback.”

After several decades of focusing on leadership training, mentorship programs and other ways to “fix” individuals, it’s time to fix the systems. That includes strengthening equity literacy, removing bias from policies and, perhaps most importantly, opening our eyes to the workplace reality. Sutton recalls giving a presentation on equity to a diverse group of about 100 people at a financial institution, which was followed directly by a discussion with the senior leadership. When the rank-and-file employees exited, the only people left in the room were white men. “They looked around and said, ‘This is such a visual.’”

6. Institutionalize beneficial practices introduced during the pandemic

While the pandemic has imposed numerous hardships on businesses and individuals, it has spurred experiments that could help propel progress on equity. Remote work, for example, has been a double-edged sword: while it has erased the lines between work and leisure (or, as Williamson puts it, “we’re not really working from home, we’re living at work”) and exacerbated the burdens of parenting, it has also brought greater time flexibility, reduced travel and opened positions to wider candidate pools, including people with disabilities or chronic illnesses and those who live in rural areas.

The trick is to lock in what works. Organizations can start by instituting flexible schedules, although diversity experts warn that such policies must be embraced by both genders if we are to avoid reinforcing stereotypes. Research from Women in Capital Markets suggests, in fact, that men want flexibility as much as women, if not more. What workers need most is not fewer hours but control of their schedules. When one investment firm banned emails, meetings and other work on Sundays in hopes of reducing long hours, women panicked, says Sutton, because many use Sundays to catch up on work pushed off their schedules by other responsibilities.

When workers do return to their offices, companies need to be both deliberate and flexible in how they manage on-site and remote staff, especially as the pandemic and its impacts evolve. As one example, at CPP Investments, we have instituted a rule that all meetings will continue to be held virtually as we gradually open our offices for access, to create a level playing field for those who remain working from home. We are focused on how to maintain equity and team cohesion in a way that balances the realities of colleagues at home with care responsibilities with the needs of those who choose to work in the office. Our hope is that while women in the past may have felt the need to step sideways or even back to gain flexibility, they may now be able to step forward while retaining flexibility.

When workers do return to their offices, companies need to be both deliberate and flexible in how they manage on-site and remote staff, especially as the pandemic and its impacts evolve.

We see some signs of optimism. One survey conducted in June found that 72% of working people believe shifts caused by COVID-19 will have a positive impact on gender equality in the workplace. In addition, almost four-in-10 said they see their company “taking steps after the pandemic to enhance gender equity as a priority in the workplace.” Let’s not allow these efforts to fall off the corporate agendas.

7. Leaders must lead

Formal sponsorship by senior executives can make a big difference to a person’s sense of inclusion, but research has shown women and minorities do not get as much exposure to top leaders as their male counterparts do. “There is nothing more valuable than having people talk about you in those rooms where decisions are made about promotions and future job opportunities,” says Catalyst’s van Biesen.

While the support of peers and immediate supervisors is critical to fostering inclusion successfully, top leaders must set the tone. There are myriad ways how executives can convey that equity matters, from personally participating in diversity programs to hosting discussions about discrimination to calling out even subtly objectionable behaviour. “This is not a women’s issue, this is our issue as a society, and as leaders we have to lend our voice and influence, we have to be exemplars in every organization,” says Luongo.

“This is not a women’s issue, this is our issue as a society, and as leaders we have to lend our voice and influence, we have to be exemplars in every organization,” says Luongo.

Something as simple as saying hi to an employee’s child when they run into camera range during a videoconference can signal that the organization empathizes with colleagues’ challenges. An executive or board member asked to speak at a conference can insist the panel be diverse.

Leaders also need to demand data on progress toward diversity goals. “They need to be clear about what they believe in for their organizations and, if the organization has adopted targets, then talk about why,” says Sutton. One chief executive went so far as to add the title Chief Diversity Officer to their own title, sending the message that diversity is not the responsibility of someone in HR three levels down, but of the CEO.

“They need to be clear about what they believe in for their organizations and, if the organization has adopted targets, then talk about why,” says Sutton.

One of the most important steps top executives can take is to ensure that equitable behaviour is the norm lower down in the hierarchy, and particularly among frontline managers. Van Biesen calls it “the frozen middle”: a management tier that can view diversity as an area of risk rather than opportunity, sees potential downside in change, and so is the hardest part of the organization to engage. “But the reality is that most people’s lives are controlled by their immediate manager, and that manager’s behaviour accounts for 45% of an employee’s experience of inclusion,” she says. Ensuring that frontline managers have bought into diversity efforts is particularly vital in the wake of the pandemic and anti-racism protests, as many employees continue to struggle with challenges beyond their jobs.

Crises can be important pivot points—sometimes for the worse. The focus on inclusion and diversity may recede as a strategic priority amid a fight for corporate survival. Boards may avoid making changes for the sake of stability. Functions that don’t directly bring revenue are usually the first to experience cutbacks, and the most recent employees with weaker connections to the corridors of power often come from non-dominant groups. At a basic human level, when threatened, we regress to experience and expedience—going back to the familiar, what worked in the past. Williamson, who used to work at a financial firm, remembers layoff decisions during the 2008 financial crisis: “It was almost tribal, a ‘we’re going to protect our own’ kind of mindset. And ‘our own’ tended to be the guys.”

CPP Investments’ forecasts suggest the Canadian economy will contract by 6% this year—a recession more than twice as deep as the one caused by the global financial crisis. There can be no lasting economic recovery without full female participation. We can learn from Japan’s recent experience in implementing its “Womenomics” plan to boost long-term growth and address a shrinking labour-force. In 2012, the Japanese government adopted a series of reforms, such as legislating greater disclosure of gender diversity data, improving nationwide parental leave policies and expanding childcare. Eight years later, the country has achieved 73% female labour-force participation, a record that surpasses the U.S. and Europe. It is now the obligation of both men and women in senior positions to champion a similar transformation in Canada and around the world.

The past few months have shown how quickly we can adapt when we must; now we need to apply the same mindset to corporate equity.

Our economies depend on it.

1 Lean In. Women are maxing out and burning out during COVID-19

2 McKinsey & Company. Most diverse companies now more likely than ever to outperform financially

3 McKinsey & Company and Lean In. Women in the workplace 2020

4 Statistics Canada. Study: Representation of Women on Boards of Directors, 2016

5 Ryerson University. Diversity Institute

6 Lean In. The state of women in corporate America

7 Catalyst. Report: Getting Real About Inclusive Leadership